It’s a frothy time in AI. OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI are raising some of the largest venture rounds ever. The appetite for AI businesses far outstrips anything else in the technology sector.

But these companies are devouring capital with no profitability in sight, and are caught in a game of margin-eroding lockstep competition.1 Most importantly, the limited revenue being created downstream of these businesses calls into question whether these businesses may grow into their valuations: David Cahn called this AI’s $200B, and later, $600B Question.

Taking this logic a step further, some people are calling the current level of investment in AI a “bubble”. I am now old enough to have heard many things referred to as “bubbles” in my lifetime, and have generally found this framing to be misleading. As with many cynical views, talk of bubbles is a good way to sound clever but miss the value. In this essay, I will:

Debunk some major historical bubbles;

Make the case that the only true, permanently-collapsing bubbles are frauds;

Suggest how things will play out in AI: we are still very early.

By analyzing Dot-Com capital investment trends as an analogy, make the case that we should expect much more capital to flow into AI.

Discuss how and why we should expect investment activity in AI to shift away from traditional venture capital and into the public markets.

2000: The Dot-Com Bubble

From about 1995 to 2000, investors were hugely excited about telecom, computing, and internet businesses, with early-stage startups routinely going public and getting enormous valuation multiples. It was an incredible time to be a technologist — until it all collapsed, and countless paper millionaires were wiped out entirely.

But how irrational was all this exuberance? The largest companies of today — Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Apple — were all significant players in the Dot-Com era. Companies like Pets.com and Webvan did go out of business, but were reincarnated a decade later as firms like Rover and Instacart, which ended up being successful in their own rights. Marc Andreessen and Bret Taylor make good cases2 that there was no categorical tech bubble, but rather a market distortion due to the Worldcom and Enron Frauds, which caused collateral damage as they collapsed.3

The dot-com bubble was the little blip on the left of this chart. Even if you had bought the top on March 30, 2000 and sat through a catastrophic drawdown — over the next two years you’d face 80% losses in most of your positions — you would’ve done extremely well in the end. Between the “top” in March 2000 and today, your Amazon position would return 203x, your Apple position 66x, etc.4 Even if your portfolio was mostly losers that went to zero, you would’ve covered your losses and then profited many, many times over.

All you had to do was nothing. But to dispassionately wait it out is no easy feat. You had to be a technology investor with a well-diversified portfolio and true long-term conviction. When most people take an 80% loss and all the pundits are sneering at them like “obviously a 200 P/E ratio was unsustainable”, their natural reaction is to sell and wash their hands of it, not to hold for another 20 years. But holding would’ve been right, in retrospect in a very predictable way: of course technology is the future, and some of the giants of the future are born today.

2008: Housing Bubble

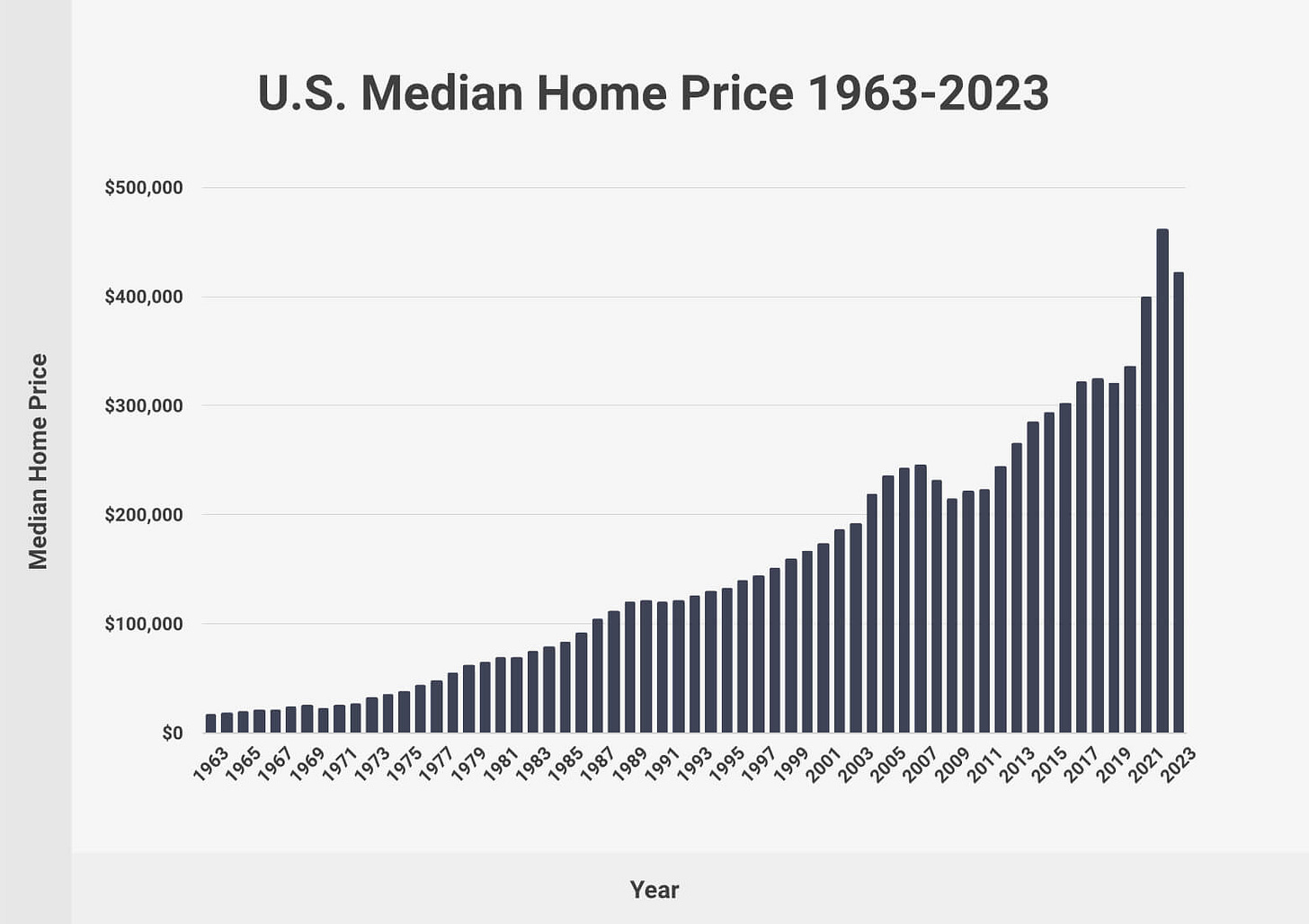

In the lead-up to the 2008 financial crisis, prices of housing in the US exploded for a variety of reasons, one of which was the easy access to (subprime) credit. Contemporary commentators spoke of a “housing bubble”, as they still do today.

In March 2020, Jesse Colombo pulled together some statistics to argue both that 2000-2007 constituted a fiscally-driven housing bubble, and that the US was due for a 2020 correction. His chart below:

The timing of this argument could not possibly have been worse! Within a few weeks, the Fed would kick off the mother of all growth cycles, and housing prices would boom even faster than before. When you zoom out, talk of a “bubble” becomes unpersuasive:

To me, this looks pretty steady. The ‘08 recession barely shows up — a short-lived drawdown in an exponential trend. All you had to do was wait through it. In retrospect, this trend seems very predictable: without profound regulatory changes that you’d be able to see coming from years away, the price of housing in the US will continue to grow just as it has for decades.

2013, 2017, 2021: Crypto

In late 2013 and early 2014, a flurry of trading activity on MtGox — the main cryptocurrency exchange of the time — briefly took the price of Bitcoin past $1,100. At the time, it seemed extraordinary. $1000 per coin? A ten billion dollar market cap? Unbelievable amounts of money. Months later, MtGox collapsed, and so did the price of Bitcoin with it. Bitcoiners soon found out that the price had been fraudulently pumped on MtGox by a trading bot that researchers named Willy.5 The price of Bitcoin fell by over 80% at its lowest, and took three-and-a-half years to reach back to $1,100. Countless early Bitcoiners lost faith during this time and thought it was over. Today, nobody remembers any of this.

On January 13, 2018, the New York Times published a memorable article: Everyone’s Getting Hilariously Rich, and You’re Not. It made fun of the wild exuberance in cryptocurrencies, with Bitcoin trading as high as $19,300 and Ethereum at $1,100. It was the first time that crypto had really hit the mainstream. People at the time thought this was a crazy bubble; I remember taxi drivers telling me what ICOs to buy.6 The market collapsed shortly thereafter, and Bitcoin would once more come down to around $3,000 in the intervening years.

Then, in 2021, following the massive COVID-era financial stimulus, crypto had another incredible run, lifting Bitcoin well past $60,000, and countless smaller cryptocurrencies along with it. This cycle too wound up with truly spectacular financial collapses, with billions of dollars incinerated at shops like Terra/Luna, Celsius, FTX, Three Arrows Capital, etc. Bitcoin would collapse down to $15,000 in the aftermath.

It is now October 2024, and Bitcoin is once more trading at $60,000, with not a peep in the popular press. The 2013 and 2017 episodes no longer look like bubbles, but mere blips on a chart. Even 2021 no longer looks like a bubble, insofar as the $60,000 price ballpark appears to be well-supported today. Similar as to the Dot-Com bubble, many positions will pan out as losses, but long-term investors with carefully diversified7 portfolios have done well.

1630: Tulips

Both crypto and the Dot-Com era have been compared to the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1630s, since that’s the one crazy bubble story that everyone knows. There are only two problems with it:

That story is 400 years old;

I’ve always been surprised that the Tulip story has had so much staying power: you’d think that a hundreds-of-years-old, niche-market story would not be highly valued as an analogy for reasoning about massive modern markets, even before historians figured out it was mostly fiction. But it’s been a very sticky — and damaging — meme. Mass enthusiasm for any kind of new technological paradigm is often metered by skepticism, and invoking Tulip Mania is always an easy dismissive reach.

The Role of Fraud

The most disastrous of all historical market bubbles was the South Sea bubble of the 1710s. But it was not just driven by speculation, but rather by massive fraud: prominent politicians were paid to pump the stock, and financial games like large-scale debt-for-equity swaps created an illusion of value.

Indeed, in virtually all other famous bubbles, fraud played a meaningful part: Enron and Worldcom set the pace for the Dot-Com bubble. FTX and others misappropriated funds to pump the prices of cryptoassets in 2021, creating fraudulent demand. The financial crisis of 2008 followed widespread mortgage and ratings fraud.

This creates some interesting framing. Frauds can create bubbles of their own, and draw a lot of speculative excess,9 but eventually collapse permanently. And it is not uncommon for big waves of technological/financial opportunity to get mixed up with some level of fraud; hot markets tends to attract grifters. However, after these frauds collapse — temporarily dragging down the market with them — the fundamental value remains. Investors in technology post-Enron, crypto post-FTX, US real estate post-2008, all have done very well.

Takeaways

Once you discount the singular story of Tulip Mania, and try to account for the impact of fraud, you are left with market histories that don’t look so crazy. It’s hard to find examples of irrational, speculative excess at scale. The popular narrative of a market bubble as a madness of the crowd, with people deluding themselves into losing their last shirt betting on magic beans — is, like a lot of other popular psychology, much more of an attractive story than grounded in fact. I think this hurts the people who believe this framing, as it excludes them from participating in episodes of great long-term wealth creation. A “bubble” is rarely a bubble.

Of course, the market can be short-term irrational, and there are fads that blow up and then collapse permanently, like the Beanie Babies craze. Those things happen all the time.

But the difference is in scale. Beanie Babies were a retail craze, not a multibillion dollar market. When there are billions of dollars of (sophisticated) capital moving into a space, there has usually been something to it. If you invest in groundbreaking technological innovation, avoid frauds, and you’re patient to hold for the long term, that tends to do well. Disruptive value creation tends to come with some volatility, and the paper-handed get shaken out over a few boom-bust cycles. The returns are captured by those who hold on and double down.

Looking back at the Dot-Com crash, or even the Railway or Automobile investment manias10 of the late 1800s and early 1900s: temporary market crashes tend to flush out many of the competing firms, but some of them survive and go on to capture the market’s long-term value. The tricky question for investors, and the reason to be well-diversified, is that it is very hard to predict ahead of any crash which firms will be the long-term winners.11

AI

By our framing of prior bubbles, the most important question is whether there is fraud. I don’t think there is. There’s no FTX injecting fake liquidity. There’s no Enron luring people with blockbuster returns. In fact, reported revenues are still quite low.

In that sense, I don’t think there’s a “bubble” in AI. In fact, I think we are still extremely early. Right now, there are still many questions about deployment, monetization, margins, commoditization, and where long-term value accrues. As those questions get answered and revenues from other parts of the economy start substantially transitioning into AI, mainstreet investors will begin to internalize just how much change is coming down the pike. Then you’ll see a much larger scale of capital inflow.

AI in the Public Markets

When I mention a much larger scale of capital inflow, what do I mean? Isn’t $6.6B already the largest venture round of all time? Wasn’t venture investment even at the peak of the Dot-Com era just $35B a year?12

People forget that private markets are much smaller than public markets, and equity markets are much smaller than debt markets. So far, all investment activity has been in private, equity markets.

During the Dot-Com era, telecom companies were spending $135B a year — $250B in 2024 dollars — on infrastructure. In aggregate, they spent around $700B that decade. These were incredible levels of raw capital expenditure on the belief that there were network effects to owning internet infrastructure. To support this extraordinary level of spend, they raised over $2T in the public markets,13 at least $600B ($1.1T in 2024) of which was in bonds (debt).

That debt came to be the big problem. Virtually all of these telecom firms were massively overlevered.14 You know how that story ended.

But the Dot-Com telecom story makes it clear that there’s a much larger scale of capital available. Just as for the advent of the internet, AI offers a globally transformational opportunity. There are some lessons to be heeded with respect to debt and leverage, but modern technology giants are much smarter about this.15 When Sam Altman said he wanted to raise 7 Trillion Dollars, the telecom era puts it into historical perspective: do I believe that the opportunity in AI is seven times larger than the opportunity in the internet? I’ll leave that question to you.

In the path of this opportunity, the capital demands are unending. Larry Ellison thinks that competing in LLMs will soon cost over $100B to enter, and he’s right. This means that some of these private firms may need to soon transition into the public markets to fundraise (and maybe even into the debt markets for those confident in their revenues and margins), just as a way of accessing sufficient capital at scale. In tech, we haven’t seen that kind of dynamic in a long time.

I think it would be interesting and good if that were to happen. Investment capital into AI would scale up significantly, but there’s also a pro-social effect. Bear in mind that the bulk of innovation is currently in hard-to-access privately held companies. There are public companies like Google, Microsoft, and Nvidia for folks to bet on, but the vast majority of investors will not have any exposure to firms like OpenAI or Anthropic for the foreseeable future. These technologies will meaningfully reshape the economy, and the perception of all the economic gains being captured by a few private companies would draw significant political heat. This transitional phase will go much smoother if mainstreet investors can have, for example, at least a little bit of exposure through their 401Ks. Regulators would be smart to help make the public markets more accessible to “democratize” this big shift.

Conclusion

It’s going to take some time for AI to percolate and revenues to transition from other parts of the economy. Between then and now, I’m sure some investors will lose patience, many firms will be outcompeted, and unexpected innovations will hit many times over. The market will have some volatility.

But overall, it is clear that, just as in the Dot-Com cycle, we are witnessing the emergence of technologies that will become the dominant forces in our economies in the coming decades. Long-term, the biggest players in AI will be the biggest companies on the planet. If I’m making sector-level bets today, I’m not going to be worried by any 2025 drawdown, for example. As usual, it’s hard to predict which firms specifically will come out on top a decade from now after some boom-bust cycles, and where in the stack they will play, but I think it’s safe to expect that well-diversified investors16 in AI will do very well long-term.

I’d call this a Red Queen Race.

I know that the Dot-Com crash happened before the frauds collapsed, but my point is that if not for those frauds pumping up the market in the first place, the Dot-Com era would’ve probably played out a little differently.

And you would’ve done much better if you hadn’t bought the literal top. Buying in 1996 would’ve scaled up your returns by another order of magnitude.

The story is incredible and I recommend reading it, if you’re into that kind of thing. They published more on Willy later, under the WizSec Security Research blog.

I remember many people at the time riffing on Joe Kennedy Sr., something along the lines of: when your shoe-shine boy is telling you which stocks to buy, it’s time to exit the market.

Because of the liquidity network effects inherent in cryptocurrencies, the emphasis here is much more on “carefully” than on “diversified”. So far, this has been the rare sector where you don’t want a market index or portfolio of many different assets.

If you don’t have an FT account: the article reviews a 2008 book called Tulipmania, the thrust of which is to historically debunk the Tulip Mania story. There’s also another article in the Smithsonian.

The word “excess” should be carefully considered, since you could argue that market participants were reacting rationally to information they believed to be truthful. The problem is that the information was false!

These present significant counterexamples to the notion that long-term investors entering hype cycles tend to do well. Though these innovations created immense value, speculation was so great, and the rate of corporate death was so great, that most early investors lost money. There were over 1,500 automobile manufacturers in the early 20th century, and the vast majority of them went out of business. At that scale, it’s very hard to assemble a diversified portfolio such that you can hit the 1-in-20 or 1-in-100 jackpot the way that Dot-Com investors did (holding many positions that went to zero, and Amazon that returned their portfolio 100+ times over).

My perspective on this is that these investment manias really suffered from insufficiently regulated markets. Fraud was everywhere; this was long before vanilla financial regulations such as fiduciary responsibilities to shareholders and insider trading laws. I suspect that had the law been more mature, there would’ve been much less fraud, and investors generally would’ve done better for that reason.

This is pretty much the thesis of Alisdair Nairn’s Engines that Move Markets, which has been on my mind as I’ve written this essay. Nairn’s framing is that when a new, disruptive technology enters a market, it’s easy to spot the losers, but hard to figure out who will be the winner.

$64B in 2024 dollars. All figures in this section will be in 1994 dollars, unless otherwise noted.

The accounting here gets pretty fussy — over $1T of the capital raised went toward acquiring competing telecom firms, not toward building out infrastructure.

The Worldcom fraud played a big role, because Worldcom’s market activity was setting the pace for all competitors. Without Worldcom’s (and Enron’s) presence or malfeasance in the market, the market would likely not have had as much leverage or subsequent volatility.

Other than Amazon, no big tech company carries net debt.

Another reason that I’d like to see more fundraising activity for AI companies transition to public markets is that so much innovation is locked in private markets at the moment, and therefore it’s hard to build a well-diversified portfolio.

Agree with a lot of this but:

1) I think it takes a very US-centric view of bubbles. Expanding outside of the US makes it clear that bubbles do happen and not just for fraud.

- For example, Japanese real estate was obviously a bubble and is still well down from it's peak 30 years ago. https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2021/02/the-defining-trait-of-all-bubbles-the-willful-suspension-of-disbelief/

- Chinese equities are still below their 2007 peak.

- Even within the US, you can point to clean tech in 2006-2011 as being a bubble. Even though we've seen an increase in renewables 10 years later, i don't think that makes this not a bubble (bubbles can be when prices get ahead of reality).

https://www.bvp.com/atlas/eight-lessons-from-the-first-climate-tech-boom-and-bust

2) I agree that Bitcoin is not bubble, but 95% of the shitcoins that went up to stupid levels were bubbles that people called out at the time and were right (ex: Dentacoin). I think it can be true that people were wrong about bitcoin but largely right about the rest (and honestly, the jury is still out about non-bitcoin crypto).

3) It's not out yet but I'm guessing a lot of the themes you discuss will be in this book by Byrne Hobart, so I'd check it out https://www.amazon.com/Boom-Bubbles-Stagnation-Byrne-Hobart/dp/1953953476

In addition to Charles's counterexamples, I would also point to a smaller subsector that could be labeled a bubble - Direct to Consumer companies. I think the largest of those companies that went public like Allbirds (-95% from peak), Warby Parker (-70% from peak), and Peloton (-98% from peak) have for the most part fared pretty horrifically after telling a story about how they deserved technology company valuations that did not pan out.

As far as I know none of those companies committed any traditional fraud, they merely overpromised and underdelivered on the basis that whatever internet technology would somehow unlock tech company level of growth for them to sell shoes / glasses / exercise bikes. I think this is more or less where I stand on generative AI as a technology. It's still too early to tell whether or not the tech will ever get mature enough to generate the returns implied by the investments. I can see the potential for it to be an infrastructure level investment akin to telecoms or going the way of Juicero - an over engineered, expensive system that you could have just had a person do more cheaply.