The Arab Spring of 2010 was a sweeping wave of protests that ended up toppling the rulers of Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Yemen. These protests were said to be largely organized over freshly-mainstream platforms Twitter and Facebook. Commentators noted that media is traditionally the “fourth estate” of government, and that social media enables a new type of citizen journalism. It became clear that newfangled social media was not a toy, but politically highly impactful.

Political discourse around social media evolved quickly. Barely three years later, in 2013, the Snowden Leaks sowed widespread distrust in internet platforms. In 2015, reports began to discuss Facebook’s data collection on behalf of Cambridge Analytica, which turned into a full-blown scandal by 2018, bringing Mark Zuckerberg to testify to congress. The Trump election had taken these suspicions to a new height, with reports of large-scale misuse (allegedly by foreign actors!) of social media for propaganda. In 2020, the US encountered the same concerns as the rest of the world for the first time, as a foreign-owned1 social media platform, TikTok, became massively popular among US citizens.

The pressure on and mistrust toward social media platforms throughout the 2010s was immense. While some regulators suggested antitrust breakups, more moderate politicians and academics often converged on regulating social media companies like public utilities. This debate went nowhere (1, 2, 3). Candidly, it seems that people stopped caring after a few years.

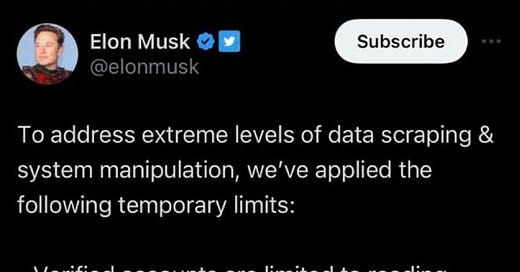

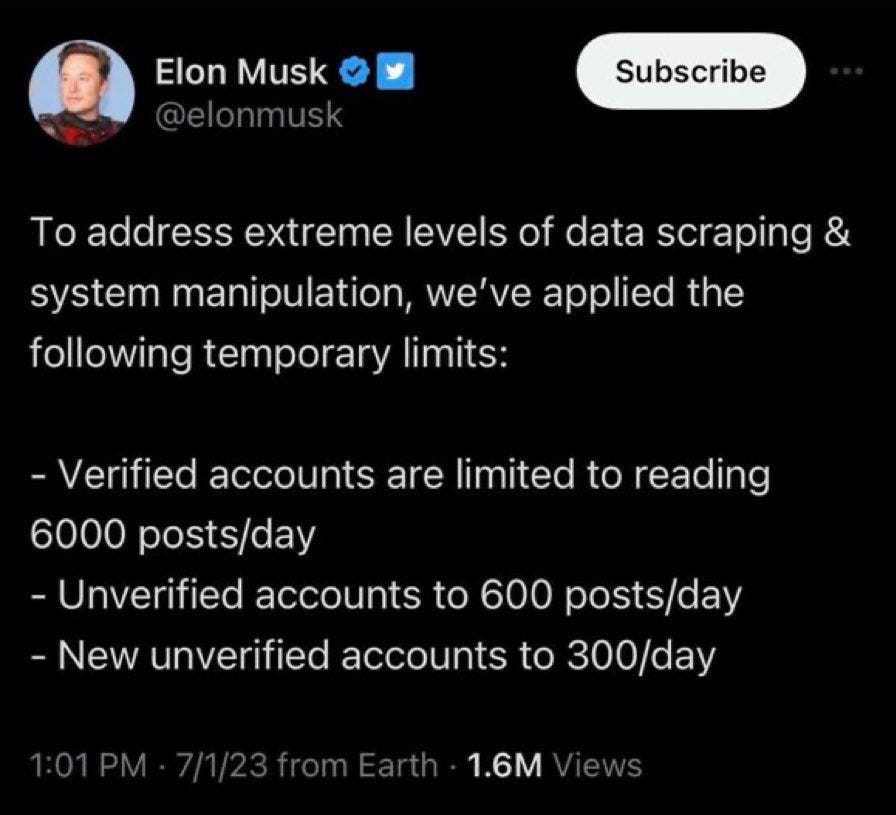

But we now have to care again! Two days ago, Elon Musk’s Twitter ceased to allow viewing tweets by users who weren’t logged in, thereby breaking millions of tweets embedded in third-party websites. Twitter’s previously liberally open APIs have been locked down, breaking countless integrations. Yesterday, Elon Musk finally applied rate limits to viewing Tweets.

This was widely ridiculed, but it’s no joke: there are countless public services that use Twitter as their primary way of broadcasting news to the world. From heads of state through police departments to weather warnings: they all rely on Twitter to send important messages to the public.2 Twitter is where news breaks. And over its nearly twenty years of existence, Twitter had built up an enormous amount of goodwill as a globally accessible, reliable service provider.

It is now clear that Twitter’s global town square is not reliable any more. There’s some chance it may go bankrupt altogether and cease to operate. But as I’m looking at this, and at the past thirteen years of politicization of social media, and at the global distrust toward the great social media platforms, I ask a question that seems strangely open: why is there not even one government-provided social media platform?

There’s plenty of precedent in normal media. It’s called Public Broadcasting. In the UK, we have the BBC. In the US, we have VOA. In Germany, we have ARD. The social media analogy to public broadcasting seems clear: a government could try to reduce their citizens’ dependence on Californian technology companies, and provide a mostly-taxpayer-funded, independently administered, politically neutral social media platform (ideally open-source!).

But there isn’t.3 I understand why we don’t have one in the US; we prefer independent private-sector solutions and lean toward having a “smaller” government. But countries like the UK, France, Germany, etc. love public-sector service providers. They’ve got the taxpayer covering health services, electric utilities, mail, rail, banking, even churches! But not social media?

As mentioned, plenty of politicians and academics want social media to be regulated like a public utility. But regulating a private-sector business to turn it into a public broadcaster-analogue is obviously unworkable in the US; the very idea of nationalizing a business is anathema to American culture. Many European regulators would love to do it, but they can’t, because these firms are outside their jurisdictions.

What is possible is good old-fashioned competition: any government4 could start its own, taxpayer-funded social media platform alternative, and run it like a public utility (with global scope). It wouldn’t be hugely expensive: for example, Twitter operated at a net loss of about $500M a year from 2013 through 2016.5 For the US, that’s $1.50 per person, per year. And frankly, especially given the endless political concern over the power of social media, it seems obvious that possessing or controlling such an entity6 is a valuable strategic asset. Imagine if you were a small, technology-forward nation, and you happened to administrate the open-source Twitter-analogue that 500 million people use to communicate every month. The geopolitical clout and consequent industrial opportunities in running a major communications channel seem significant.

That, by itself, is not an argument that there should be a government-provided social media platform. I just think that it’s weird that there isn’t. We have many dozens of countries that have expressed hand-wringing regulatory desire for social media platforms. They could easily borrow the analogy of public broadcasting, and build an alternative. From a resources and policy perspective, it’s entirely feasible: it’s just software. You’d think that somebody somewhere would’ve done it by now, after fifteen years of scandals and political grandstanding at the highest levels globally.

So, why doesn’t it exist? Can nation-states simply not build software? That can’t be true. Is there the defeatist assumption that they can’t? Maybe. Is any proposal going to die on the vine because it’d be a gigantic design by committee? Maybe. Would questions of moderation tie the whole thing up in endless free speech litigation? Maybe.7 Is the whole thing just posturing, and politicians and academics want to complain and not actually do anything? Maybe.

I’m somewhat stumped. I can’t get to a clear reason why there isn’t even one, other than noting that it’s symptomatic of a loss of state capacity. For previous great technical innovations in information broadcasting, e.g. the telephone, radio, or television, governments were generally quick to follow private-sector innovations and to put the taxpayer dollar behind building up reliable institutions to support the cutting edge of technology. But not for social media. Strange.

Finally, there is a decent argument for a government-provided social media platform, even if it’s just as a fallback for when the private-sector ones falter. The argument follows the fact that we are currently exiting a Zero Interest-Rate Policy environment. That puts downstream pressure on technology businesses like Reddit and Twitter8 that have existed as unprofitable quasi-utilities for a decade-plus: they may now actually have to make money. And that pushes them to make deeply unpopular decisions like both Reddit and Twitter’s in the past weeks. Some of these decisions, particularly API retrieval restrictions, lock out the general public from benefiting from the data that they have contributed to these platforms, which is one of the most striking indicators that maybe a commonly-owned platform might not be a bad idea.

There is an old Silicon Valley joke that Twitter had the highest ratio of creating public value to capturing it. Perhaps a public-sector figure will recognize that some of these social media platforms may simply never successfully monetize, or may capture value only in ways that their users dislike, which creates a large user experience gap that can be filled by… a product that doesn’t have to make money. Abstractly, the domain of infrastructure that benefits everyone but structurally struggles to make profits, such as the postal service, has historically fit pretty squarely into the scope of public-sector projects. I wonder if we will ever see a serious public-sector attempt, or if the state capacity just isn’t there, anywhere.

To be clear, what I mean here is that historically, virtually all social media companies of note were unambiguously American. As such, other countries had already for years been navigating their citizens spending big chunks of their time and personal data on foreign social media platforms. TikTok, owned by Chinese parent Bytedance, is the first time that the US is navigating a situation where its citizens are spending big chunks of their time and personal data on a foreign social media platform. The TikTok situation is extra politically charged for the Americans because the foreign platform is Chinese, which carries more foreign-relations political tension at present than if TikTok were e.g. French or Brazilian.

In some sense, Twitter is the fully-featured version of RSS that really succeeded. Twitter had become the high-volume free alternative to traditional Press Release/News Wire services, and the journal of record for updates from virtually any organization. Verification badges were simple and could be trusted. Twitter’s format was perfect for organizations to publish short-form updates and invite commentary, more so than the format provided by any other social media platform.

I’m excluding TikTok/Bytedance for the purposes of this piece (where I think the dynamic is more complex), even though the argument could be very well made for it.

Note that doesn’t even have to be a government at the country-level. Even the government of a large city would have sufficient resources.

Source: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitter-statistics/

Or even just knowing that nobody else is controlling it! You can see that strategic value in the level of nervousness that politicians in non-US countries have about Facebook, or the same in the US about TikTok.

Countries with clearer/simpler free speech legal standards would be in a better position to implement moderation subject to their legal system.

Even this very platform, Substack, appears to be deeply unprofitable and may soon be in a precarious financial position. The news came out just today that 2013-founded popular service Gfycat shuts down on September 1 of 2023. There are concerns even about the Internet Archive shutting down, albeit for other reasons. While it is inexpensive to run software and store data, there exist substantive concerns for the longevity of many of the internet platforms that we have enriched as a commons. Losing them over amounts of money that are insignificant at the tax/budget level would be a shame.

There was a panel on Public Digital Space, organized by the European Cultural Foundation this year. Here is a link to the event and the participants: https://debalie.nl/programma/peter-pomerantsev-how-we-connect-in-the-public-digital-space-02-06-2023/

CSPAN works pretty well, so I don't see why not.